Crater Chronicles: Using Europa’s Youngest Craters to Measure Irradiation Timescales

A classic example of irradiation-induced alteration of exogenic material on Europa’s trailing hemisphere is the so-called radiolytic sulfur cycle. In this process, sulfur ions from Io are implanted into Europa’s icy surface by Jupiter’s magnetosphere, where continued irradiation breaks down the sulfur and water ice, producing hydrated sulfuric acid along with various sulfur-bearing intermediates. Over time, these products are expected to reach a steady-state equilibrium—a balance between production and destruction under constant bombardment.

But how long does it actually take to reach this equilibrium?

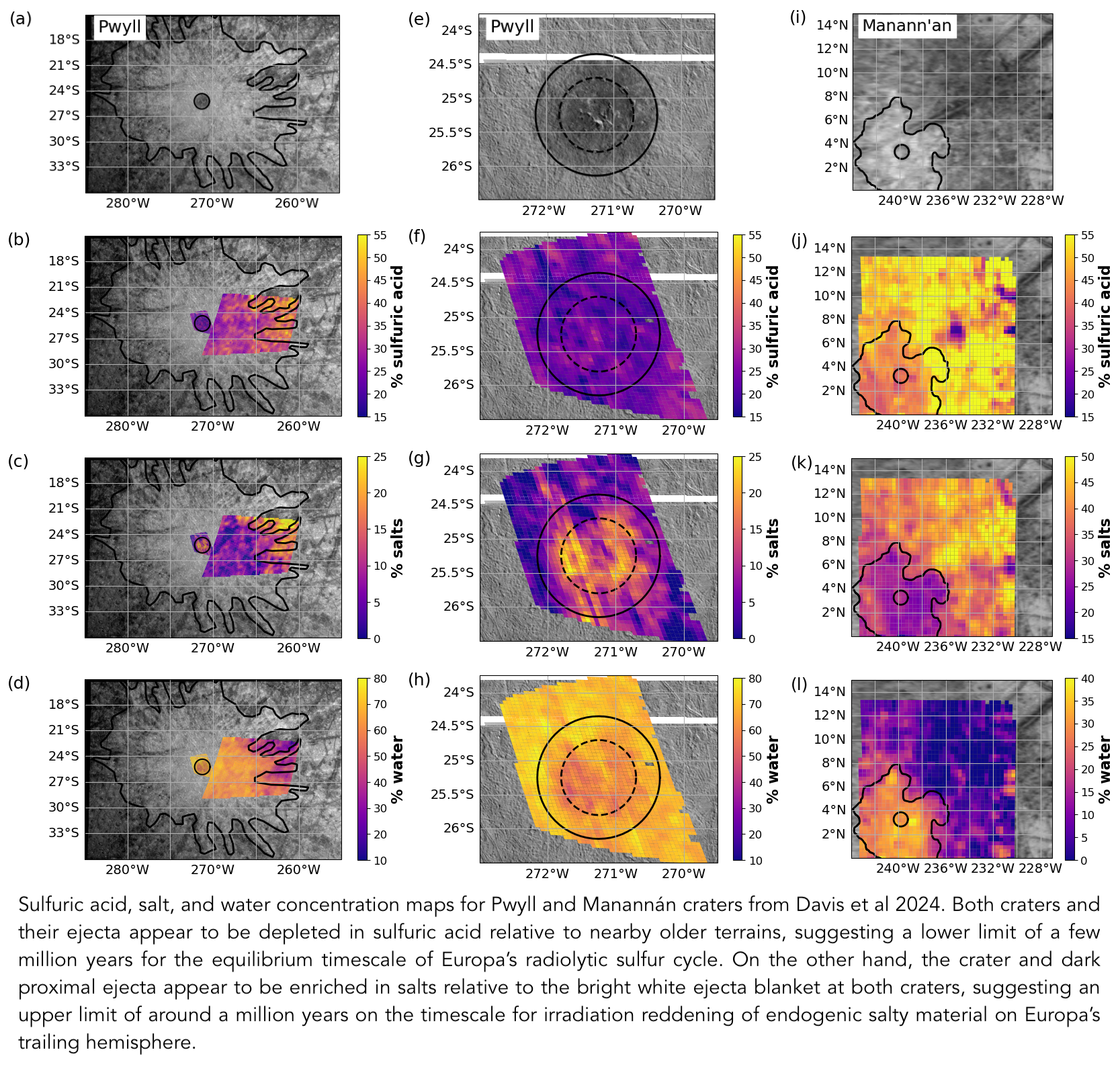

In our recent paper (Davis et al. 2024), we used Galileo/NIMS infrared spectra to analyze the composition of Europa’s youngest impact craters Pwyll and Manannan. We found that both the crater floors and their surrounding ejecta blankets are significantly depleted in hydrated sulfuric acid compared to adjacent older terrains. This suggests that sulfuric acid has not yet had enough time to accumulate to equilibrium levels within these young geologic features.

Using age estimates for the craters, we place a lower limit of several million years on the timescale for Europa’s sulfur cycle to reach equilibrium — a value that is orders of magnitude longer than previous estimates from laboratory experiments.

Interestingly, while sulfuric acid is missing, the dark proximal ejecta around both craters appear enriched in salts relative to their bright, icy ejecta blankets. These excavated salty materials show signs of irradiation-induced darkening and reddening, similar to what is seen in Europa’s chaos terrains and bands. Assuming that these salts were initially unirradiated when excavated by the crater forming impact, this places an upper limit of ~1 million years (the age of Pwyll crater) on the timescale for salt irradiation darkening which suggests it is a much faster process than the buildup of sulfuric acid.

These results demonstrate that different irradiation-driven processes operate on very different timescales on Europa’s surface: salts darken and redden quickly, while the accumulation of sulfuric acid is comparatively slow. This has important implications for interpreting Europa’s surface composition and for identifying fresh exposures of ocean-derived material in future missions.